Casual Inference Data analysis and other apocrypha

Don't stop as soon as you hit stat sig! How to safely stop an experiment early with alpha spending in Python

Where it begins: The (understandable) urge to stop early

Let me tell you a story - perhaps a familiar one.

Product Manager: Hey

{data_analyst}, I looked at your dashboard! We only kicked off{AB_test_name}a few days ago, but the results look amazing! It looks like the result is already statistically significant, even though we were going to run it for another week.Data Analyst: Absolutely, it’s very promising!

Product Manager: Well, that settles it, we can turn off the test, it looks like a winner.

Data Analyst: Woah, hold on now - we can’t do that!

Product Manager: But…why not? Your own dashboard says it’s statistically significant! Isn’t that what it’s for? Aren’t we like…95% sure, or something?

Data Analyst: Yes, but we said we would collect two weeks of data when we designed the experiment, and the analysis is only valid if we do that. I have to respect the arcane mystic powers of ✨

S T A T I S T I C S✨!!!

Has this ever happened to you?

If you’re a working data scientist (or PM), it probably has. This is an example of early stopping, or optional stopping, or data peeking - and we are often cautioned to avoid it. The most frustrating part about this conversation is that it happens even when both parties are trying to be collaborative and play by the rules.

From the data scientist’s point of view, they did a power analysis and figured out how to make sure the experiment is as informative as possible. Can’t we just stick to the plan?

From the PM’s point of view, the dashboard is telling them that statistical analysis sanctions the result they see. We gave each experiment arm a chance, and one of them was the winner using their usual statistical process. Why should we wait for the full sample if an easy win is right in front of us?

The PM’s argument, frankly, makes a lot of sense. A couple more detailed arguments in favor of stopping early might look like this:

- If we think that one of the treatment groups really is better, then collecting more data is an unnecessary waste. Collecting data isn’t usually free - so it’s best to stop as soon as you can.

- If we think that one of the treatment groups really is better, than we should make it available to a larger population as soon as we can. This is not always just a question of a small gain, or a few more dollars. In clinical trials, the stakes can be very literally life or death - the trials of the HIV drug AZT were stopped short for this reason, as the results were so overwhelmingly positive that it seemed unethical to continue depriving the control group and other patients of the chance at an effective therapy. The trial was ended early and the FDA voted to approve its use shortly after (there are also more complicated factors involved in that RCT, but that’s another conversation).

The core issue here comes from the fact that good experimentation needs to balance speed vs risk. On the one hand, we want to learn and act as quick as we can. On the other, we want to avoid unnecessary risk - every experiment includes the possibility of a downside, but we want to be careful and not take on more risk than we need to.

All the possible experimentation procedures sit somewhere on this high speed-low risk tradeoff spectrum. The “highest speed” solution would be to avoid experimentation at all - just act as quick as you can. The “lowest risk” solution would be to run the experiment as planned, and always run it by the book, no matter what happens.

As is so often the case, there is a chance to get the both of worlds by picking a solution between the extremes. There are good reasons to stop a test early, but in order to do so safely, we need to be more careful about our process. Let’s start by looking at the risks of stopping early without changing our process, and then we’ll talk about how to mitigate those risks.

What risk do we take by stopping as soon as the result is significant?

Let’s remind ourselves why we do statistical significance calculations in the first place. We use P-values, confidence intervals, and all of those kinds of other frequentist devices is because they control uncertainty. The result of designing an experiment, picking a sample size based on 80% power and doing your calculations with $\alpha = 5\%$ is that the arcane mystic powers of statistics will prevent you from making a Type I error 95% of the time and a Type II error 80% of the time.

Talking about the benefits in terms of “Type I” and “Type II” errors is a little opaque. What does this do for us here in real life? We can make it concrete by talking about a more specific analysis. Let’s talk about an analysis which is very common in practice - comparing the means of two samples experimentally with a T-test. A T-test based experiment usually looks something like this:

- Pick your desired power and significant levels, usually denoted by the magic symbols $\beta$ and $\alpha$. We often use $\beta = 80\%$ and $\alpha = 5\%$, though you may pick other values based on the context.

- Use your favorite power calculator to pick a sample size, which we’ll call $n$.

- Collect $n$ samples from the control and treatment arms, and compute the difference in means $\hat{\Delta} = \overline{y^T} - \overline{y^C}$. That’s just the mean of the treated units, minus the mean of the control units.

- Use your favorite implementation of the T-test (like the one in scipy) to compute a P-value. If $p \leq \alpha$, then you can conclude that $\Delta \neq 0$, and so the treatment and control groups have different population means. Assuming the differences goes in the direction of better outcomes, you officially pop the champage and conclude that your treatment had some non-zero effect compared to control. Nice!

This procedure is a test run “by the book”, in which we collected all our data and ran a single T-test to see what happened. It guarantees that we get the usual magic protections of P-value testing, namely that:

- We’ll only come to a false conclusion $\alpha\%$ of the time. That is, it will only rarely happen that the above procedure will cause us to pop the champagne when in fact $\Delta = 0$. This is protection from Type I errors, or “false detection” errors.

- We’ll detect effects that actually exist (and are larger than the MDE) about $\beta \%$ of the time. That is, if $\Delta$ is large enough, we’ll pop the champage most of the time. This is protection from Type II errors, or “failure to detect” errors.

What happens to these guarantees if we introduce the possibility of early stopping? The short version is that the more often we check to see if the result is significant, the more chances we are giving ourselves to detect a false positive, or commit a Type I error. As a result, just checking more often can cause our actual Type I error rate to be much higher than $\alpha$.

Let’s look at the actual size of the impact of early stopping. Let’s augment our T-test based experiment by not just calculating the p-value on the last day, of the experiments but on the 29 days before. We’re going to simulate this example in a world where the null hypothesis really is true, and there is no treatment effect.

So at each step of a simulation run (where one step is one day, and one simulation run is one experiment), we’ll:

- Simulate 100 samples from the $Exponential(5)$ distribution and append them to the control data set. Do the same for treatment. Since we’re drawing treated and control samples from the same distribution, the null hypothesis that they have the same population mean is literally true.

- Run a T-test on the accumulated treatment/control data so far. If $p < .05$, then we would have stopped early using the “end the experiment when it’s significant” stopping rule.

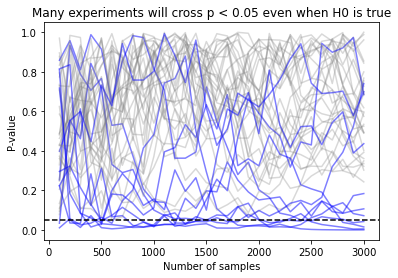

If we do this many times, this will tell us whether stopping as soon as we see a significant result would have caused us to commit a Type I error. If we run this many times, and track the P-value of each run, we see that the trajectory of many P-values crosses the .05 threshold at some point early on in the test, but as time goes on most of the P-values “settle down” to the expected range:

In this picture, each simulation run is a path which runs from zero samples to the total sample size. Paths which cross the $\alpha = .05$ line at any time would have been false positives under early stopping, and are colored blue. Paths which are never significant are shown in grey. You’ll notice that while few paths end below the dotted line, many of them cross the line of significance at some point as they bob up and down.

During these simulations, the T-test conducted at the very end had a false positive rate of 5%, as expected. But the procedure which allowed stopping every day (ie, every 100 samples) had a false positive rate of 27%, more than 5x worse! (I ran 1000 simulations, though I’m only showing 40 of them so the graph isn’t so busy - you can find the code in the appendix, if you’re curious.)

We talked about the speed-risk tradeoff before - adding more checks without changing anything else will expose us to more risks, and make our test results much less safe. How should we insulate ourselves from the risk of a false positive if we want to stop early?

On first glance, this looks similar to the problem of multiple testing that might be addressed by methods like the Bonferroni correction or an FDR correcting method. Those methods also help us out in situations where more checks inflate the false positive rate. Those methods would cause us to set our $\alpha$ lower based on the number of checks we’re planning to run. By lowering $\alpha$ we are “raising the bar” and demanding more evidence before we accept a result. This is a good start, but it has a serious flaw - it will meaningfully decrease the power ($\beta$) of our experiment, and we’ll need to run it longer than expected. Can we do better?

We can try and compromise by saying that we should be skeptical of apparent effects early in the experiment, but that effects that are really large should still prompt us to stop early. That leaves us a little wiggle room - we should not stop early most of the time, unless the effect looks like it is really strong. What if we set $\alpha$ lower at the beginning of the experiment, but used the original value of $\alpha$ (5%, or whatever) after all the data is collected? That sort of “early skepticism” approach might get us a procedure that works.

Of course, the devil is in the details, and so this opens us up to the next question. How strong does the effect need to be early on in the experiment for us to be willing to stop early? How should we change our testing procedure to accommodate early stopping?

The $\alpha$ spending function approach: set the standard evidence higher early on in the experiment

The idea we’ve come across here is called the alpha spending function approach. It works by turning our fixed significance level $\alpha$ into a function $adjust(p, \alpha)$, which takes in the proportion of the sample we’ve collected so far and tells us how to adjust the significance level based on how far along we are. The proportion $p$ is given by $p = \frac{n}{N}$, the fraction of the total sample collected.

The idea here is that when $p$ is small, $\alpha$ will be small, and we’ll be very skeptical of observed effects. When we’ve collected the entire sample then $p = 1$ and we’ll apply no adjustment, meaning $adjust(p, \alpha) = \alpha$. A detailed reference here is Lan and DeMets 1994, which focuses on the clinical trial setting.

What form might $adjust(p, \alpha)$ have? Since we want it to scale between 0 and $\alpha$ as $p$ increases, a reasonable starting point is something like:

\[adjust_{linear}(p, \alpha) = p \alpha\]We might called this a linear alpha spending function. Lan and Demets above mention an alternative called the O’Brien-Fleming (OBF) alpha spending function, which is:

\[adjust_{OBF}(p, \alpha) = 2 - 2 \Phi (\frac{Z_{\alpha / 2}}{\sqrt{p}})\]Where $\Phi$ is the CDF of a standard normal distribution, $Z_{\alpha/2}$ is the Z-value associated with $\alpha/2$, and $p$ is the fraction of the sample we’ve collected so far.

In Python, a little bit of assembly is required to calculate this function. It looks something like this:

def obf_alpha_spending(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

z_alpha_over_2 = norm.ppf(1-desired_final_alpha/2)

return 2 - 2*(norm.cdf(z_alpha_over_2/np.sqrt(proportion_sample_collected)))

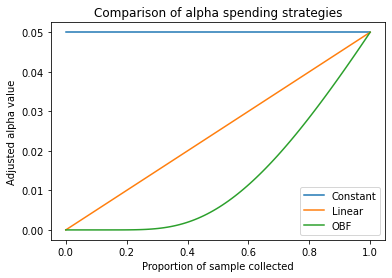

Unless you spend a lot of time thinking about the normal CDF, it’s probably not obvious what this function looks like. Lets see how going from $p=0$ (none of the sample collected) to $p=1$ (full sample collected) looks:

We see that the OBF function is more conservative everywhere than the linear function, but that it is extra conservative at the beginning. Why might this be? Some intuition (I think) has to do with the fact that the relationship between sample size and precision is non-linear (the formula for the standard error of the mean, for example, includes a $\sqrt{n}$).

Okay, so we have a way of adjusting $\alpha$ dependign on how much data has arrived. Lets put it to the test. We’ll rerun the simulation above, with the following conditions. This time, we’ll compare the false positive rates from the different strategies we’ve discussed: constant alpha (same as above), the linear spending function, and the O’Brien Fleming spending function. The results of 10,000 simulated experiments look like this:

| Method | Number of False positives (of 10k simulations) | False positive rate (Type I error rate) |

|---|---|---|

| Constant $\alpha = .05$ | $2776$ | $27.76\%$ |

| Linear | $1285$ | $12.85\%$ |

| OBF | $799$ | $7.99\%$ |

In the first row, we see what we already know - early stopping without using an alpha spending rule has a False positive rate much larger than the expected 5%. Linear alpha spending is an improvement (about 2.6x more errors than desired), but OBF is the winner, with a Type I error rate closest to 5% (1.6x more errors than desired). OBF will have less power, but power analysis subject to early stopping rules is a subject for another time.

The alpha spending approach is an easy thing to add to your next test, and it’s worth doing - it lets you have the best of both worlds, letting you stop early if the result is large at only a small cost to your false positive rate. And given that you can write it as a 2-line Python function, it’s not too hard to add to your A/B test analysis tool. And best of all, having a strategy for early stopping means no more awkward conversations about the arcane mystic powers of ✨S T A T I S T I C S✨ with your cross-functional partners!

Appendix: Code for the simulations

P-value paths

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind, norm

import pandas as pd

days_in_test = 30

samples_per_day = 100

def simulate_one_experiment():

treated_samples, control_samples = np.array([]), np.array([])

simulation_results = []

for day in range(days_in_test):

treated_samples = np.append(treated_samples, np.random.exponential(5, size=samples_per_day))

control_samples = np.append(control_samples, np.random.normal(5, size=samples_per_day))

result = ttest_ind(treated_samples, control_samples)

simulation_results.append([day, len(treated_samples), result.statistic, result.pvalue])

simulation_results = pd.DataFrame(simulation_results, columns=['day', 'n', 't', 'p'])

return simulation_results

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

n_simulations = 40

false_positives = 0

early_stop_false_positives = 0

for i in range(n_simulations):

result = simulate_one_experiment()

if np.any(result['p'] <= .05):

early_stop_false_positives += 1

color = 'blue'

alpha = 0.5

else:

color = 'grey'

alpha = .3

if result.iloc[-1]['p'] <= .05:

false_positives += 1

plt.plot(result['n'], result['p'], color=color, alpha=alpha)

plt.axhline(.05, linestyle='dashed', color='black')

plt.xlabel('Number of samples')

plt.ylabel('P-value')

plt.title('Many experiments will cross p < 0.05 even when H0 is true')

print('False positives with full sample:', false_positives / n_simulations)

print('False positives if early stopping is allowed:', early_stop_false_positives / n_simulations)

Plotting the OBF function

from scipy.stats import norm

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

def constant_alpha(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

return desired_final_alpha

def linear_alpha_spending(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

return proportion_sample_collected * desired_final_alpha

def obf_alpha_spending(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

z_alpha_over_2 = norm.ppf(1-desired_final_alpha/2)

return 2 - 2*(norm.cdf(z_alpha_over_2/np.sqrt(proportion_sample_collected)))

p = np.linspace(0, 1, 100)

alpha = .05

plt.plot(p, [constant_alpha(alpha, pi) for pi in p], label='Constant')

plt.plot(p, [linear_alpha_spending(alpha, pi) for pi in p], label='Linear')

plt.plot(p, [obf_alpha_spending(alpha, pi) for pi in p], label='OBF')

plt.legend()

plt.xlabel('Proportion of sample collected')

plt.ylabel('Adjusted alpha value')

plt.title('Comparison of alpha spending strategies')

Type I error comparison of different alpha spending functions

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import ttest_ind, norm

from tqdm import tqdm

def constant_alpha(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

return desired_final_alpha

def linear_alpha_spending(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

return proportion_sample_collected * desired_final_alpha

def obf_alpha_spending(desired_final_alpha, proportion_sample_collected):

z_alpha_over_2 = norm.ppf(1-desired_final_alpha/2)

return 2 - 2*(norm.cdf(z_alpha_over_2/np.sqrt(proportion_sample_collected)))

def simulate_one(control_average, alpha_strategies, samples_per_day, number_of_days, desired_final_alpha):

total_sample_size = samples_per_day * number_of_days

results = {f.__name__: 0 for f in alpha_strategies}

control_samples, treatment_samples = np.array([]), np.array([])

for day in range(number_of_days):

control_samples = np.concatenate([control_samples, np.random.exponential(scale=control_average, size=samples_per_day)])

treatment_samples = np.concatenate([treatment_samples, np.random.exponential(scale=control_average, size=samples_per_day)])

for alpha_strategy in alpha_strategies:

alpha = alpha_strategy(desired_final_alpha, len(control_samples) / total_sample_size)

if ttest_ind(control_samples, treatment_samples).pvalue <= alpha:

results[alpha_strategy.__name__] = 1

return results

simulation_results = pd.DataFrame([simulate_one(control_average=5,

alpha_strategies=[constant_alpha, linear_alpha_spending, obf_alpha_spending],

samples_per_day=100,

number_of_days=30,

desired_final_alpha=.05) for _ in tqdm(range(10000))])

print(simulation_results.mean())

print(simulation_results.sum())