Casual Inference Data analysis and other apocrypha

Getting started with multiple hypotheses - Methods that control the FWER and their costs

Multiple hypothesis testing shows up frequently in practice, but needs to be handled thoughtfully. Common methods like the Bonferroni correction are useful quick fixes, but they have important drawbacks that users should understand. *What do methods like Bonferroni and Bonferroni-Holm do, and why do they work? What alternatives are there?

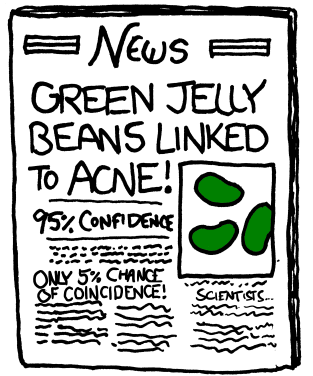

Banner from XKCD 882.

Multiple testing is everywhere, and can be tricky

Any time we compute a P-value to test a hypothesis, we run the risk of being unlucky and rejecting the null hypothesis when it is true. This is called a “false positive” or “Type I error”, and we carefully construct our hypothesis tests so that it only happens 1% or 5% of the time - more generally, that it happens $\alpha%$ of the time. There’s an analogous risk for confidence intervals; we might compute an interval that doesn’t cover the true value, though again this shouldn’t happen too often.

Almost as soon as we start thinking of data analysis as opportunities to test hypotheses, we encounter situations where we want to test multiple hypotheses at once. For example:

- When we have an A/B test with more variants than just “Test” and “Control” and we want to compare them all to each other

- When we want to compare the out-of-sample error rates of multiple machine learning models to each other

- We want to known what happens when we choose one of the many possible subsets of features in a ML model

- When we want to look at the significance of many coefficients in a multiple regression at the same time

However, this needs to be handled more carefully than simply computing a pile of P-values and rejecting whichever ones are smaller than $\alpha$. For any given hypothesis test, we have a false positive rate of $\alpha$; we spend a lot of time making sure our test procedures keep the likelihood of a false positive below $\alpha$. But this guarantee doesn’t hold up when we test multiple hypotheses.

For example, let’s say we examine two distinct null hypotheses, which are both true. Even though $H_0$ is true, we run an $\alpha$ probability risk of rejecting each one. If the test statistics are uncorrelated, this means that our chance of any false positives is $1 - (1-\alpha)^2$. If $\alpha = .05$, for example, this means that we have a 9.75% chance of at least one false positive. This problem gets worse the more simultaneous tests we run - if we run enough tests, we’ll eventually find a null hypothesis to reject, even when all the nulls are true. This has the unfortunate implication that the more questions we ask, the more likely we are to get an answer that rejects a null hypothesis, even when all the null hypotheses are true. To borrow a quote without context, “seek, and ye shall find” - though what you find may be spurious.

Here’s a stylized example of the problem:

This is a classic example of multiple testing error - if you test 20 times at the 5% significance level, you’ve got a much better chance of finding a spurious non-null relationship, and all your usual guarantees about “only happening 5% of the time” are no longer valid.

A simulation example: Estimating multiple means

Let’s take a look at a simulated example to see this kind of problem in action. Then, once we have some possible solutions, it will be easy to see

We’re going to simulate $n = 30$ draws of 5 random variables, which we’ll call $X_1, X_2, X_3, X_4, X_5$. All of these variables will be normally distributed, and have a variance of 1. The first 4 will have a mean of zero, and last one will have a mean of one half. We’ll test the 5 hypotheses that the mean of each individual group is zero. This means that in this example, four of the five null hypotheses are true (the null is true for all the variables but X5).

First, let’s write a function to simulate the data:

from scipy.stats import ttest_1samp, sem, norm

def generate_dataset():

n = 30 # As we know from Intro Stats, 30 is infinity

X1, X2, X3, X4, X5 = norm(0, 1), norm(0, 1), norm(0, 1), norm(0, 1), norm(.5, 1)

X1_samples, X2_samples, X3_samples, X4_samples, X5_samples = X1.rvs(n), X2.rvs(n), X3.rvs(n), X4.rvs(n), X5.rvs(n)

return X1_samples, X2_samples, X3_samples, X4_samples, X5_samples

And create a function to calculate which of the P-values are significant:

def calculate_significance(X1_samples, X2_samples, X3_samples, X4_samples, X5_samples, alpha):

p_values = np.array([ttest_1samp(X1_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X2_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X3_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X4_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X5_samples, 0)[1]])

is_significant = p_values < alpha

return is_significant

Which we can run in order to create a whole lot of simulated datasets and whether we reject our five null hypotheses for each one:

n_sim = 10000

significant_simulations = list()

for _ in range(n_sim):

significant_simulations.append(calculate_significance(*generate_dataset(), alpha=.05))

significant_simulations = np.array(significant_simulations)

Great. That’s 10000 simulations of the kinds of inferences we’d make in this situation.

X1_rejected = significant_simulations[:,0]

X2_rejected = significant_simulations[:,1]

X3_rejected = significant_simulations[:,2]

X4_rejected = significant_simulations[:,3]

X5_rejected = significant_simulations[:,4]

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X1: {0}'.format(np.mean(X1_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X2: {0}'.format(np.mean(X2_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X3: {0}'.format(np.mean(X3_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X4: {0}'.format(np.mean(X4_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X5: {0}'.format(np.mean(X5_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times we falsely rejected any null hypotheses: {0}'.format(np.mean(X1_rejected | X2_rejected | X3_rejected | X4_rejected)))

Output:

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X1: 0.0516

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X2: 0.0515

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X3: 0.05

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X4: 0.051

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X5: 0.7473

Proportion of times we falsely rejected any null hypotheses: 0.1905

Lets break that down: For each individual true null hypothesis, we rejected the null hypothesis around 5% of the time, the expected false positive rate. For X5, which does not have a mean of zero, we correct reject the null about 75% of the time - so we have about 75% power for X5 with this mean. While each individual test retains its correct false positive rate, we have a high probability of reporting at least one false positive. This seems like a problem - our analysis will report at least one false positive almost 20% of the time!

This last quantity - the proportion of times we falsely reject any null hypotheses - has a special name. We call it the Family-wise Error Rate, or the FWER. It’s one way to define the “false positive rate” for multiple experiments. Usually, when we refer to “controlling the FWER”, we mean a testing procedure which would keep the FWER below $\alpha$.

FWER isn’t the only way to think about false positives in multiple tests. Another option is to try and control the number of rejected hypotheses which are false positives (defined as Number of False rejections / Number of all rejections). This quantity is called the “False Discovery Rate” (FDR), and it’s worth thinking about as a less strict alternative to the FWER. But that’s a story for another time. For now, let’s talk about how we can control the FWER using a method familiar to many who have encountered this problem before - the Bonferroni correction.

A common fix: Bonferroni correction to control the FWER

The fundamental issue is that when we test more things, we’re more likely to get at least one false positive. One way to solve this is to set the bar higher - if we are less likely to reject the null hypothesis overall, we’ll be less likely to make a false positive.

How much higher should we set the bar? That is, how should we change $\alpha$ in order to account for the increased false positive rate?

The most common solution is the Bonferroni correction. The fix is simple - if we want an FWER of $\alpha$, and we want to test $m$ hypotheses, then we set each test’s significance level to $\frac{\alpha}{m}$. This results in an FWER that is not more than $\alpha$, and is easy to implement, as we see in an updated version of our example:

def calculate_significance_bonferroni(X1_samples, X2_samples, X3_samples, X4_samples, X5_samples, alpha):

p_values = np.array([ttest_1samp(X1_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X2_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X3_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X4_samples, 0)[1],

ttest_1samp(X5_samples, 0)[1]])

is_significant = p_values < alpha/5.

return is_significant

n_sim = 10000

significant_simulations = list()

for _ in range(n_sim):

significant_simulations.append(calculate_significance_bonferroni(*generate_dataset(), alpha=.05))

significant_simulations = np.array(significant_simulations)

X1_rejected = significant_simulations[:,0]

X2_rejected = significant_simulations[:,1]

X3_rejected = significant_simulations[:,2]

X4_rejected = significant_simulations[:,3]

X5_rejected = significant_simulations[:,4]

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X1: {0}'.format(np.mean(X1_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X2: {0}'.format(np.mean(X2_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X3: {0}'.format(np.mean(X3_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X4: {0}'.format(np.mean(X4_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X5: {0}'.format(np.mean(X5_rejected)))

print('Proportion of times we falsely rejected any null hypotheses: {0}'.format(np.mean(X1_rejected | X2_rejected | X3_rejected | X4_rejected)))

Output:

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X1: 0.0107

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X2: 0.0108

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X3: 0.0087

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X4: 0.0103

Proportion of times that we rejected H0 for X5: 0.5082

Proportion of times we falsely rejected any null hypotheses: 0.0398

We see that:

- The FP rate for each individual test is now $\frac{\alpha}{5} = \frac{.05}{5} = .01$.

- The FWER was successfully reduced to below $\alpha$.

- The power was reduced - we only successfully rejected the null for X5 50% of the time, compared with 75% of the time without the correction. Since power decreases as we set $\alpha$ lower, this is not too surprising.

This example highlights the main tradeoff that we make in choosing FWER-controlling methods like the Bonferroni correction. We can control the FWER and be unlikely to report a false positive, but we are also less likely to report a true positive. As we add more hypotheses, the power gets lower because $\alpha$ decreases. This trade of FWER control for lower power might make any inference impossible when the sample size is small or the number of hypotheses is large, as the power is reduced too much to do anything useful. This tradeoff is not always the right one to make! The last section points out some alternative approaches that are commonly used by the FWER-skeptical.

Why does the Bonferroni correction work?

It’s worth a quick recap of the proof that the Bonferroni correction keeps the FWER below $\alpha$. The wikipedia page has the proof, but I found it helpful to break it down step by step. If you’re not interested in the proof, feel free to skip to the next section.

We’d like to show that when we set the significant level to $\frac{\alpha}{m}$, the FWER is not more than $\alpha$. We can break down an FWER violation as the union of all events where one P-value of a true $H_0$ is less than the significance level. In the following, let’s define:

- $m$, the total number of hypotheses we want to test

- $m_0$, the total number of null hypotheses which are true

- $p_i$, the p-value for hypothesis $i$

- $\alpha$, the significance level set by the analyst

Our goal is to demonstrate that the FWER when we apply the Bonferroni correction is less than $\alpha$, and we want to avoid making any assumptions about the structure of the dependence between hypotheses.

| $\mathbb{P} (\bigcup_{i=1}^{m_0} p_i \leq \frac{\alpha}{m})$ | This is the definition of the FWER under the Bonferroni-correction. |

| $\leq \sum_{i=1}^{m_0} \mathbb{P}(p_i \leq \frac{\alpha}{m})$ | This is a result of the Union Bound.1 |

| $= m_0 \frac{\alpha}{m}$ | Because $\mathbb{P}(p \leq X) = X$ when $H_0$ is true. |

| $\leq m \frac{\alpha}{m} = \alpha $ | Because $m_0 \leq m$, the number of true null hypotheses is $\leq$ the total number of hypotheses. |

What about confidence intervals?

So far we’ve talked about simultaneously testing a number of hypotheses by computing a number of P-values. You might wonder whether the procedure is any more complicated if we’re interested in simultaneous confidence intervals, rather than P-values. It turns out that the Bonferroni procedure works without any real change if you’re computing confidence intervals - all you need to do is change the significance level of all your intervals to $\frac{\alpha}{m}$.

If you’re interested in a deeper look at the confidence interval case, take a look at 2.

A more powerful procedure for P-values: Bonferroni-Holm

The Bonferroni correction has a lot going for it! It’s easy to use and explain, which is always a positive attribute for a method. However, we noticed that it tends to reduce the power. Since its introduction, this has lead researchers to look for methods that are more powerful than the Bonferroni correction, but which still control the FWER. The most popular competitor is the Bonferroni-Holm method, which uses a similar principle but is often more powerful than the simple method we outlined.

The BH procedure works something like this:

- Sort all the P-values you computed from your tests in ascending order. We’ll call these $P_1, …, P_m$, and they’ll correspond to hypotheses $H_1, …, H_m$.

- We’ll define a series of significance levels $\alpha_1, …, \alpha_m$, where $\alpha_i = \frac{\alpha}{m + 1 - i}$.

- Starting with $P_1$, see if it is significant at the level of $\alpha_1$. If it is, reject it and move on to testing $P_2$ at $\alpha_2$. Continue until you find a hypothesis you can’t reject, and stop there.

- Put another way: If $k$ is the first index such that we can’t reject $H_k$, then reject all the hypotheses from $1, …, k-1$.

Bonferroni-Holm can be meaningfully more powerful than the simple Bonferroni correction. The reason for this is that we’re being most strict on the tests that are most likely to lead to a rejection, and more lenient on the ones with a little less evidence, while still controlling the FWER. The exact amount of additional power can vary quite a lot, though. 3

The Bonferroni-Holm method is easy to use in Python - you can do it in one line of Statsmodels. All we’d need to do in the code above to switch to Bonferroni-Holm instead of the usual correction is to do:

from statsmodels.stats.multitest import multipletests

is_significant = multipletests(p_values, method='holm', alpha=.05)[0]

At the end of the day, if you’re testing a large number of hypotheses with P-values and want to control the FWER, you should always use Bonferroni-Holm over the normal Bonferroni correction. Unfortunately, unlike the ordinary Bonferroni correction, it’s not immediately obvious how to use the Bonferroni-Holm procedure with confidence intervals. This SE answer provides some possibilities, though it points out that there are multiple ways of doing it stated in the literature.

FWER control procedures other than Bonferroni and Bonferroni-Holm

Bonferroni and Bonferroni-Holm are not the only available methods for controlling the FWER. This was quite a rich subject of research in the 70s and 80s, when many researchers devised methods that improved on these two.

- The Šidák correction is an alternative to Bonferroni with very, very marginally more power. It does make more assumptions about the dependence structure between the hypotheses (that they are independent, see 4)

- The Hochberg procedure is a variation on BH that is also implemented in Statsmodels, but similarly makes some assumptions about the dependence between the hypotheses.

A theme here is that Bonerroni and Bonferroni-Holm are so valuable in part because their lack of strong assumptions about the relationships between hypotheses. Some dependencies are so common, though, that they have their own tests:

- The Shaffer procedure is used for collections of tests with logical dependencies, such as all pairwise comparisons between groups. It is general and quite powerful as pairwise comparison methods go, but it is computationally costly and tricky to implement. The computational challenges are addressed here.

- Tukey’s test is another option for all pairwise comparisons.

- In the specific caes where we want to compare all variants to a “reference” variant (such as “all test variants vs control”), we can use Dunnett’s test.

Unfortunately, none of these specialized methods are in Python - there is a version of Tukey’s test in the statsmodels sandbox, but I don’t think it’s tested.

What alternatives might we use instead of the FWER? The FDR and Hierarchical model approaches

FWER is an intuitive analogue to the usual False Positive (Type I Error) rate. However, methods like Bonferroni control the FWER at substantial cost. In cases where there are hundreds or thousands of simultaneous hypotheses, they may set an extremely high bar. There are at least two lines of criticism against the FWER, which lead us to some alternatives.

Criticism 1: The FWER reduces our power substantially and is not the most relevant quantity. What we care about is knowing how many of the claimed null effects after examining the data might be spurious. The thing we should control is the Total number of spurious rejections / Total number of all rejections in any given case. This line of criticism has found great success in settings where the number of hypotheses run into the hundreds or thousands, as in microarray studies. It leads to the False Discovery Rate as an alternative to the FWER which is both more relevant and more powerful.

Criticism 2: Type I error rates of point null hypotheses are not what we care about - the null hypothesis isn’t ever true and knowing something is “not zero” isn’t much information. We care about high-quality estimates of the parameters. The problematic aspects of multiple comparisons disappear if we view them from a Bayesian Perspective and fit a hierarchical model that uses all the information in the data. Instead of controlling the Type I error rate, we should introduce a prior which avoids us from making extreme claims.

Since this is a criticism of the Type I error paradigm, it’s not just an issue with FWER, but is one aspect of a broader criticism of NHST. My favorite bit of writing on this is Andrew Gelman’s Why we don’t (usually) need to worry about multiple comparisons. I find this to be a compelling criticism of NHST and the classical perspective; I myself commonly use and advocate for Bayesian methods. Nonetheless, even as a card carrying Bayesian the methods outlined here are useful both because people use these methods often, and because MCMC on a large dataset is costly but a quick P-value calculation might not be.

Endnotes

1: The basic idea here comes from our intuition about set theory: $\mathbb{P}(A_1 \cup A_2) = \mathbb{P}(A_1) + \mathbb{P}(A_2) + \mathbb{P}(A_1 \cap A_2) \leq \mathbb{P}(A_1) + \mathbb{P}(A_2)$

That is, the size of the union set is less than or equal to the sum of each individual set’s size, since the union doesn’t include “duplicates” (the intersection).

2: With an extra definition and some artful hand-waving, I think an analogous proof for the CI case might look like:

\[\mathbb{P} (\bigcup_{i=1}^{m} \mu_i \notin CI_{\frac{\alpha}{m}}(X_i) )\] \[\leq \sum_{i=1}^{m} \mathbb{P}(\bigcup_{i=1}^{m} \mu_i \notin CI_{\frac{\alpha}{m}}(X_i) )\] \[= m \frac{\alpha}{m} = \alpha\]Where we’ve defined $CI_{\frac{\alpha}{m}}(X_i)$, the confidence interval of random variable $i$ at the $\frac{\alpha}{m}$ level.

More generally, a simultaneous CI procedure was constructed for arbitrary contrasts between variables in this paper.

3: From Holm’s paper (p.4):

The power gain obtained by using a sequentially rejective Bonferroni test instead of a classical Bonferroni test depends very much upon the alternative. It is small if all the hypotheses are ‘almost true’, but it may be considerable if a number of hypotheses are ‘completely wrong’. If $m$ of the $n$ basic hypotheses are ‘completely wrong’ the corresponding levels attain small values, and these hypotheses are rejected in the first $m$ steps with a big probability. The other levels are then compared to $\alpha / k$ for $k = n -m, n-rm-l, n-rm -2, …, 2, 1$, which is equivalent to performing a sequentially rejective Bonferroni test only on those hypotheses that are not ‘completely wrong’.

4: The proof for Šidák’s method is pretty straightforward, once we set it up.

We want a FWER rate of $\alpha$. Let’s define $\alpha_S$ as the Šidák-corrected value that we want to find. If all of the $m$ the tests are independent, then the FWER is given by:

\[1 - (1 - \alpha_S)^{m} = \alpha\]Which we can rearrange to get:

\[1 - (1 - \alpha)^\frac{1}{m} = \alpha_S\]Giving us the corrected $\alpha$. Unfortunately, this correction produces procedures that are almost exactly as powerful as the Bonferroni method.

Written on July 22nd , 2020 by Louis Cialdella