Casual Inference Data analysis and other apocrypha

Causal Inference

Causal inference is everywhere you look

Despite its lofty and technical name, causal inference seems to come naturally to us. Children are constantly trying things out - with no prompting to do so, you’ll find them messing with everything in grabbing range - pets, toys, pots, pans, sounds, etc. In addition to the pleasure of causing chaos, they are often learning along the way, discovering by throwing things about that some objects bounce and other objects shatter. When data scientists engage in similar activity, we usually call it “causal inference”, if only for the benefit of our own dignity. Even creatures more intelligent than data scientists (dolphins, cats, etc) are known to engage in similar behavior, learning how things work by trying them out and observing the consequences. This behavior comes so easily to us because understanding cause and effect is core to how we make decisions and navigate the world.

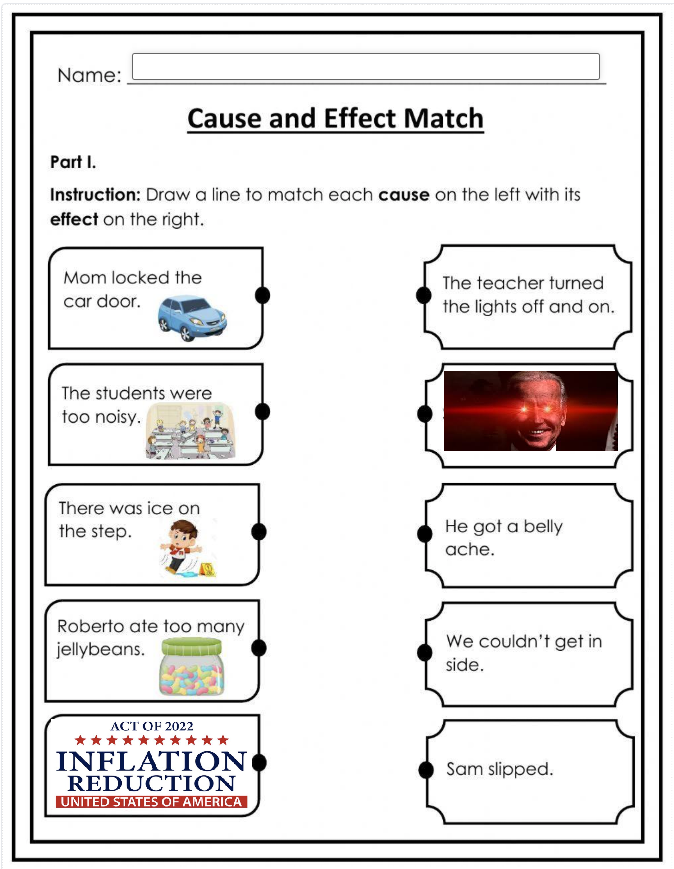

More sophisticated examples of inferring cause and effect show up in our lives all the time. Americans recently had to evaluate the actions of the late Biden administration, and we spent a lot of time talking about whether the Biden team’s decisions produced good effects or bad ones. For example, most Americans were concerned about inflation; had the administration taken the right steps to deal with it? For example, had the very clearly named Inflation Reduction Act actually done what it claimed to do? Looking at a graph of inflation over time, it seems plausible at first glance:

[Add a plot of inflation over time, with a dotted line for the IRA]

Looking at this chart, we see that between A and B, the inflation rate came down from X to Y. Does that mean that the IRA caused inflation to drop by Y - X points?? If so, that would be pretty remarkable.

The election is over, so it is of course the perfect time to consider this question. Unfortunately, I’m not an economist, so frankly I’m not the ideal person to answer it. But here in the United States we have a grand old tradition of non-experts trying their hand at something new and getting embarrassingly out of their depth, so it is my civic duty to try.

There’s another reason I picked this question. In theory, at least, the country in which I reside is a democracy (the precise status of said democracy is currently a subject of lively debate, but we’ll save that for another day). It seems to me that a democracy will function better if the people in it can both delegate some tasks to experts (like economists) while also still having the ability to verify them.

Okay, so what do the experts say about the Inflation Reduction Act? Googling for about a second indicates that a handful of economists asked said that it did not affect inflation, citing some of the factors like the price of energy as the real drivers. From first principles, it’s not hard to see why given what was actually in the bill. Well, that’s strange - inflation actually did come down, right? Doesn’t that suggest it had some role? Let’s look at some data that will help us answer this question.

How would we know if the Inflation Reduction Act decreased inflation? Counterfactuals and causal assumptions

“Did the IRA decrease inflation?” is actually a pretty complex question, though it looks simple at first glance. How would we begin to answer it? One way to try and make sense of it is to think of it as a counterfactual scenario - what would have happened to inflation if the IRA had not been enacted, all else being equal? If we knew how this counterfactual scenario would have played out, we can compare it to the factual scenario - ie, our universe - and see how big the difference is.

In causal inference-speak, we call the outcomes of these two scenarios the potential outcomes. We obesrved one of the potential outcomes when the IRA was enacted. If we want to think about the IRA’s effect on interest rate on day $t$, then we can calculate the treatment effect:

\[\underbrace{\Delta_t}_{Effect} = \underbrace{y_t^1}_{Inflation \mid IRA} - \underbrace{y_t^0}_{Inflation \mid No \ IRA}\]If we had the power to step into an alternate universe to observe the other potential outcome (where the IRA was not enacted), we could calculate the effect. The fundamental problem of causal inference is that we don’t - we only have the information from our universe. The most common approach to solving this problem is to run a randomized experiment, and then attempt to estimate the average value of the effect. The randomization helps us by making sure that all other variables are ignorable, ie that do not confound our estimate. An experiment is an attempt to “simulate” multiple universes where we control the conditions.

We can’t run such an experiment, as we only have one US economy and zero time machines. So we need to control in our analysis for all the things an experiment would have controlled for. What else could have affected our inflation?

- Supply chain challenges in the US

- Energy price

- Interest rate

- Other global factors, which also affected similar countries

We can double check out logic by putting these together in a DAG with dagitty

We’re going to create an predicted counterfactual

I’ve collected the relevant time series data in this sheet:

Computing a counterfactual with CausalImpact

https://github.com/WillianFuks/tfcausalimpact

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GTgZfCltMm8

The following code shows no effect; what’s missing? Canada’s inflation rate, maybe

https://www.bankofcanada.ca/rates/price-indexes/cpi/

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/06/inflation-stats-usa-and-world/

Link paper here; you could probably do a plausible version of it on your own with an AR-X model

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv(r'C:\Users\louis\Downloads\CausalImpact Demo - Inflation Reduction Act - Joined dataframe.csv')

import causalimpact

clean_df = df.rename({'US Inflation rate': 'y',

'Gasoline Spot price': 'x1',

'Fed Interest rate': 'x2',

'GSCPI': 'x3',

'Canada inflation rate': 'x4',

'UK inflation rate': 'x5'}, axis=1)

clean_df = clean_df[['y', 'x1', 'x2', 'x3', 'x4', 'x5']]

impact = causalimpact.CausalImpact(

data=clean_df,

pre_period=[0, 213],

post_period=[214, 240])

print(impact.inferences['post_preds_means'].dropna())

impact.plot()

This tells a very different story from our initial estimate; the effect is not statistically significant, and even the point estimate is … instead of … points

Different types of effect: Point effects (esp at end), total effects, relative effects

Stress testing our counterfactual model: Placebo trials and assumption robustness

Important assumptions:

- DAG is correct

- More specifically none of the things we control for are downstream of the treatment variable in the DAG

- No confounding, ie the IRA was the only thing that acted on inflation which is clearly incorrect. Is it possible some other cause would close that gap between the counterfactual and factual scenarios? Probably yes because it’s like 2 points and inflation is nuts

Placebo

Sensitivity

Causal inference is everywhere you look, and now you get to do it too

Draft ideas

CausalImpact - https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/research.google.com/en//pubs/archive/41854.pdf

TFP version in Python - https://github.com/google/tfp-causalimpact/blob/main/docs/quickstart.ipynb

Generate counterfactual via time series modeling, fit on pre-treatment period

y_t = (linear?) local trend + local level from seasonal state space model + f(covar)

Local level is something like AR(1) plus lagged terms for seasonal components

Rubin perspective: We are filling in the other half of the potential outcome equation

Pearl perspective: We are controlling for cyclic effects, the same things that affect parallel time series, and any other factors we include as covariates

Written on th, by Louis Cialdella